About the Project

This website is still under construction - Please imagine that it is still the 1990s and this is Geocities...

The HTTP 451 response code is an indicator of the continued power of nation states to restrict the flow of media in online settings. Despite claims of being “world wide,” the Web is still segmented and differently experienced by users across the world. Website operators may face many challenges in determining if specific national and regional laws should be applied, and how to do so. The full stack analytical approach offers Web researchers a mechanism to locate these indications of the state’s continued power to better understand how code and law become intertwined. Full stack analyses may be useful to other Internet researchers, but the flexibility of the approach means that it may offer generative insights to studies of other forms of new media as well. By looking across multiple layers of the stack, this method shows how online content blocking can be directly made visible to the user but becomes inscribed within code and protocols as well. The Web is not, and perhaps never has been, truly global. The individual nation-state still matters and exercises its power within online spaces—even at the level of the protocol—to control where and how media can move.

The below text is based on Microsoft Word's version of exported HTML. It is likely not not fully display correctly :(

I hope to clean this up and make it prettier in the near future.

You can download a copy of this write-up here: HTTP-451_2022-05-09.pdf (PDF, 788 KB)

Abstract

Despite its name describing it as “world wide,” the Web is not, and perhaps never has been, truly global. The individual nation-state still matters and exercises its power within online spaces—even at the level of the protocol—to control where and how media can move. The Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) is the major technological backbone to the World Wide Web and describes the technical standards for computers to follow and exchange hypertext documents with each other. A recently adopted HTTP standard, the “451 – Unavailable for Legal Reasons” response code, shows that legal structures of the nation operate in online spaces and represents the continued restrictions on the flow of media through the Web. Though the extent of its actual implementation remains difficult to determine, the existence of the HTTP 451 status code represents the intertwined nature of law, technology, and cultural practices and prompts us to consider the corporate and government powers that are inscribed within the technical standards of the Web itself. I argue that the 451 code shows that the Web has not eliminated the significance of national borders and in fact has enabled entirely new fine-grained control over how media does and does not move. A secondary goal of this paper is to introduce the “full stack analysis” as a model of Web history research in which the protocols and technical underpinnings of the Web are confronted alongside the immediately apparent text to piece together a more expansive view of online media. By studying the implementation of HTTP 451 status codes across multiple levels of the Web stack, I show how law and regulation continue to operate online.

“Governments derive their just powers from the consent of the governed. You have neither solicited nor received ours. We did not invite you. You do not know us, nor do you know our world. Cyberspace does not lie within your borders. Do not think that you can build it, as though it were a public construction project. You cannot. It is an act of nature and it grows itself through our collective actions.”[1]

-- John Perry Barlow, “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace”

“With his symbolic helmet numbered 451 on his stolid head, and his eyes all orange flame with the thought of what came next, he flicked the igniter and the house jumped up in a gorging fire that burned the evening sky red and yellow and black.” [2]

-- Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451

As the technologies and cultural practices of the early World Wide Web were being developed, there were many utopian ideals about what this new mode of communication might bring about. Prominent among these imaginations of the early Web were the discourses of globalization and the transcending of national boundaries. For example, Howard Rheingold’s account of dialing into the WELL (Whole Earth ‘Lectronic Link) and forming virtual communities in the “electronic frontier” that spanned great geographical distances typifies the techno-utopian discourses that surrounded the Internet and the early Web.[3] Yet in the decades that followed, these utopian ideals have been reimagined and critiqued as the actual realities of the Web became more apparent.

Despite these claims of being “world wide,” the reality of the modern Web is significantly more constrained. The technical standards of the Web, alongside the cultural practices of the users, corporations, and platforms which both navigate and provide its content provide numerous examples of how the earlier promises of this (then) new form of media have failed to be realized. The Web has not been a force of widespread liberation and in fact, the technology has created more opportunities for surveillance and control.[4] The contemporary Web is significantly more ambivalent than the version that was idealized and imagined in the late 20th century.

On the one hand, the Web has provided some opportunities for users to engage in cultural practices and exchange media beyond what may have been possible in offline contexts due to physical and/or legal limitations. But on the other hand, access to some parts of the Web remains heavily constrained and continues to be restricted by local and nation-specific laws and other regulations. The lingering influence of the nation-state within the online settings of the Web can be found in the actual text of a website, such as cookie notices for compliance with the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) requirements.[5] However, traces of the nation and its continued power to control access and to restrict the flow of media can be found in the code and protocols of the Web itself.

The Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) was originally developed by Tim Berners-Lee in 1989 and represents the major technological backbone to the World Wide Web.[6] HTTP describes the technical standards for computers to follow and exchange hypertext documents with each other. One feature of HTTP is the status code that is returned to the Web browser along with the requested content to provide information about whether the request was successful (e.g. 200 – OK), if and how something went wrong (e.g. 307 – Temporary Redirect, 404 – Not Found, or 500 – Internal Server Error). In 2015, a new HTTP status code was proposed and formally adopted in early 2016: “451 – Unavailable for Legal Reasons.” Though the number 451 is a direct allusion to Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, a dystopian novel about book-burning, the status code is a more subtle form of controlling media movement rather than overt government censorship. While the HTTP 451 code emerged from a context of governments enacting legal restrictions on the Web, these laws are simultaneously intertwined with corporate power and interests.

The written standard for the HTTP 451 code states that it should be returned “when a server operator has received a legal demand to deny access to a resource or to a set of resources that includes the requested resource.”[7] This HTTP status code brings the legal structures of one nation into online spaces and represents the continued restrictions on the flow of media through the Web. Though the extent of its actual implementation remains difficult to determine, the existence of the HTTP 451 status code represents the intertwined nature of law, technology, and cultural practices. Corporate and government powers are inscribed within the technical standards of the Web and work to restrict the flow of information and media.

Accordingly, this paper centers its analysis on the HTTP standard and the prevalence of the HTTP 451 status code. I examine how the status code has been described in the written standard, how it has been perceived by website operators, and what actual implementations of the 451 code look like in practice. I argue that the 451 code shows that the Web has not eliminated the significance of national borders and in fact has enabled entirely new fine-grained control over how media does and does not move, and which users (and for which reasons) have more privileged access. When a 451 status code is displayed to a Web user it is more than just a sign of restricted content, but a reminder of the continued power of governments and corporations to control the movement of media even within online settings.

The HTTP 451 error code provides a new perspective to situate the Web within its global contexts, and may provide Web historians an approach to look beyond a website’s text alone to study how content moves (and doesn’t move) throughout the Web. As such, a secondary goal of this paper is to make the case for what I am describing as a “full stack analysis.” This analytical approahc adopts the concept of a “stack” from computer science contexts into a media and cultural studies framework. This model of Web history research is one in which the protocols and technical underpinnings of the Web are confronted alongside the immediately apparent text to piece together a more expansive view of online media.

In the following sections, I use the HTTP 451 response code to demonstrate that the cultural meanings of a given media technology can emerge from multiple layers. Attending to the Web page that is displayed to a user as well as the underlying code and protocols can reveal how government power continues to operate in online spaces. First, I discuss early optimistic visions of the Web as a borderless space and how these views have been critiques. National borders and the nation state still matter significantly on the Web. Next, introduce my model of full stack analysis as a method to study content restrictions on the Web. Then, after briefly discussing the history of the HTTP standard, I analyze many examples of how the HTTP 451 response code was introduced and eventually implemented throughout the Web. By seeking out real-world examples of how the response code appears to actual users as well as the underlying protocol that accompanies it, I show how law and regulation continue to operate online across multiple layers of the Web stack.

Techno-Utopian Visions (and Critiques) of the World Wide Web

Technologies comprise more than their standards, protocols, and technical definitions; they must also be understood as cultural objects and through the ways in which people have described and imagined them. The argument I am developing here focuses on a small part of the HTTP protocol—the response code—as a way to interrogate the extent of global access to media via the Web. However, my framing of a “full stack analysis” offers a way to expand outward from this seemingly narrow scope to consider how lower levels of the stack, such as the HTTP standard, interact with higher level cultural relations—such as regulation and law, in order to control access to and flows of media in online spaces. A full stack analysis offers a framework to see how technical standards and cultural imaginations both mutually construct and reinforce one another. This study of the HTTP 451 response code and the geographic restrictions to Web content contributes to prior critiques of the utopian visions of the World Wide Web.

During the Internet’s development and especially during its rapidly growing popularity in the 1990s, there were many idealistic beliefs about the potential of a decentralized global communications network and its reshape relations of power. John Perry Barlow’s “Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace,” which I quoted in the introduction, nicely encapsulates this techno-utopian viewpoint.[8] The online world was different and more empowering precisely because it was supposedly disconnected from real-world power structures such as the nation-state. As Rod Carveth and Michel Metz put it, “The Internet from its earliest stages was designed to be inexpensive and uncontrollable, by people who believed that the collective will and wisdom of the users was superior to the arbitrary power of supervisors.”[9] Howard Rheingold’s influential ethnography of his own experiences finding, forming, and maintain communities across large geographic distances indicates that there has been at least some truth to these techno-utopian visions in some circumstances.[10] However, these techno-utopian imaginations of the Internet are, ultimately, only imaginations.

Perceptions of the Internet as a new frontier with endless opportunities have been met with many important critiques. Much like Fredrick Jackson Turner’s romanticization of the American western frontier and his lamentation that it would no longer exist in the same way, these techno-utopian views overlook the fact that the electronic frontier is not just an empty space with resources “there” for the taking. Conditions for access often rest on exclusion and exploitation of others. In the case of the Web, the power of the nation state—in the form of law and regulation—continues to be a driving force in controlling what media can flow, and to whom.

The lingering influence of traditional institutions of power, such as the nation, even within online spaces is unsurprising given new media’s lineage from earlier technologies. In Lisa Gitelman’s discussion of new media, she rightfully points out that, “using media also involves implicit encounters with the past that produced the representations in question.”[11] There has been significant work that draws from this understanding of new media to point out that techno-utopian perceptions of technology are not universal and that in fact there are many ways that the spread of new media technologies such as the Web has reproduced and strengthened inequalities from the physical world. To name just a few examples, Alexander Moena has shown how the Internet has reinforced heteronormativity and traditional gender norms.[12] Elizabeth Ellcessor has considered the (in)accessibility of media, arguing that there is no such thing as a singular user experience and we cannot assume that technology will improve experiences for all people.[13] Ruha Benjamin, André Brock, Safiya U. Noble, and countless others have challenged views of online communication as a post-race space.[14] Megan Sapnar Ankerson sums up the situation when she states that, “Today’s web is very different from the one Berners-Lee imagined in 1989.”[15] Contrary to early idealistic visions of the Web, traditional power structures and relations have persisted online.

One way we see these continued power dynamics is in the continued influence and role of the nation state and the reach of the state to enact laws and other regulatory actions which determine what parts of the Web people have access to. This continued influence of the nation state can be seen in the visible content of the Web, such as GDPR privacy notices, enforcement of copyright law, and the seizure of Web domains involved in illegal activities.[16] The power of the state is also made apparent in the specifications of the Web as well, and the HTTP 451 status code is a technical and cultural marker of this continued power of the nation to control the movement of media in online spaces.

Content Blocking and Media Regulation

Law and the Internet have long been intertwined with one another. From its origins as a DARPA project responding to Cold War fears, the Internet’s development has always been closely related to government interests.[17] This is seen both directly and indirectly. For example, Tarleton Gillespie argues that enforcement of international copyright law no longer happens only within courtrooms, but within the design of technology and networks as well.[18] Conversely, the United States’ laissez-faire approach of the 1990s toward online regulation has been credited for enabling our experiences of the modern Internet.[19] The fact that governments’ decisions to regulate (or not regulate) can have such a significant influence on the Internet emphasizes the ongoing role of the nation even in online spaces.

Significantly, the nation continues to play an important role in restricting how media is able to move online. Geoblocking content has become widely accepted as standard practice on the Internet, often with the direct goal of copyright compliance. As Marketa Trimble puts it, “because differences among national laws persist, a need for borders on the internet, and therefore for geoblocking, seems unavoidable.”[20] And, as Evan Elkins has shown in the context of DVD region codes, such restrictions can be “consciously, intentionally, and artificially installed” within a technology itself.[21] There is no technical requirement for DVDs to be restricted to certain regions of the world, but these affordances were deliberately built into the DVD standard. Code and law become one and the same.[22] In the context of the Web, the HTTP 451 response code serves a similar function. It is a way for the power of the state to control media flows to become inscribed within the lower layers of a media technology.

Toward a Full Stack Model of Web Histories

To best understand how government control of media becomes inscribed within the Web, it is necessary to view the Web as multi-layered; we must consider both the visible layers (the web page a user sees) and the lower layers of code and protocol. I describe this approach as “full stack analysis,” and in this section briefly sketch my guiding principles. Lisa Gitelman cautions media scholars that when media become naturalized or essentialized, the underlying protocols become invisible.[23] This invisibility makes it possible for the cultural imaginaries of a given technology, such as the techno-utopianism of the Web, to evade critique.

The field of software studies seeks to challenge the essentialism of new media by specifically centering the underlying application code as a cultural object. As Manovich explains, “if we want to understand contemporary techniques of control, communication, representation, sumulation, analysis, decision-making, memory, vision, writing, and interaction, our analysis cannot be complete until we consider this software layer.”[24] One example of this line of reasoning is Jonathan Sterne’s analysis of the MP3, in which he homes in on the specifications and cultural meanings of a specific file format.[25] I follow this same thinking in my conceptualization of a full stack analytic framing.

In computer science contexts, a “stack” refers to a collection of software, protocols, or other technologies that are necessary for a certain application. A stack comprises a hierarchy of layers, where each layer uses the one below it, and supports the one immediately above it. For example, the OSI (Open Systems Interconnection) model describes seven conceptual layers that comprise most telecommunication systems: physical connection, data link, network, transport, session, presentation, and application.[26] At the lower layers, physical connections (such as copper or fiber optic cables) enable data link standards (such as ethernet), which eventually enable higher-level protocols such as HTTP, which in turn delivers the content a user eventually sees. My methodology of full stack analysis does not strictly follow pre-existing stacks such as the OSI models, but follows the conceptual framework of a hierarchy of layers. The cultural significance of a media technology can emerge from all levels of a stack. To understand the continued role of the state in regulating the flow of media on the Web, we must look at the page content itself, but also the underlying HTTP protocol.

I acknowledge that my suggestion here is hardly novel. There has been significant work that considers the highest layers of the Web stack; this includes any research that considers Web content that is visible to users, such as the Web history methodologies suggested by Niels Brügger.[27] There has also been much work at the lowest layers of the Web stack; this includes studies of the physical infrastructures of the Internet, such as the work of Lisa Parks and Nicole Starosielski.[28] With this full stack analysis, I want to consider what happens among the middle layers of technical protocols—that is, above the physical connections of the Internet, but below the content that is most visible to users. Valuable insights into the cultural significance of the Web can be elucidated by doing history across multiple layers of the stack. If we want to understand the continued ability of governments to restrict the flow of media on the Web, we must look below the page content and to the HTTP protocol itself.

The HTTP 451 Standard

Most day-to-day users of the Web are able to focus on the specific content of the websites they browse and the details of these protocols are often left entirely invisible. Yet the underlying code and protocols can reveal the ideologies that are inscribed within a given technology. The Hypertext Transport Protocol (HTTP) was developed in 1989 and is the backbone to the World Wide Web, and indeed to much of how our modern experiences of the internet happen.[29] Turning our attention to layers of code that operate “below” the visible website can still reveal much about how the power of the nation state can still operate in online contexts.

This sort of software studies approach can involve novel methodologies and strategies of reading texts. Lev Manovich takes the position that people with coding experience may have an advantage when studying the role of software in society.[30] While there is truth to this assessment, I also hope to avoid practices of academic gatekeeping and do not want to suggest that the full stack analytical frame requires highly specific technical expertise. While I have grossly oversimplified many of the specifics of how HTTP works throughout this paper, what I hope to show is that the full stack approach to Web history does not necessarily require a full understanding of computer science and networking concepts. Even without full technical expertise, a historian of the Web may still find value in widening the scope of their analysis to consider the cultural significance that lies below the most visible layers of page content.

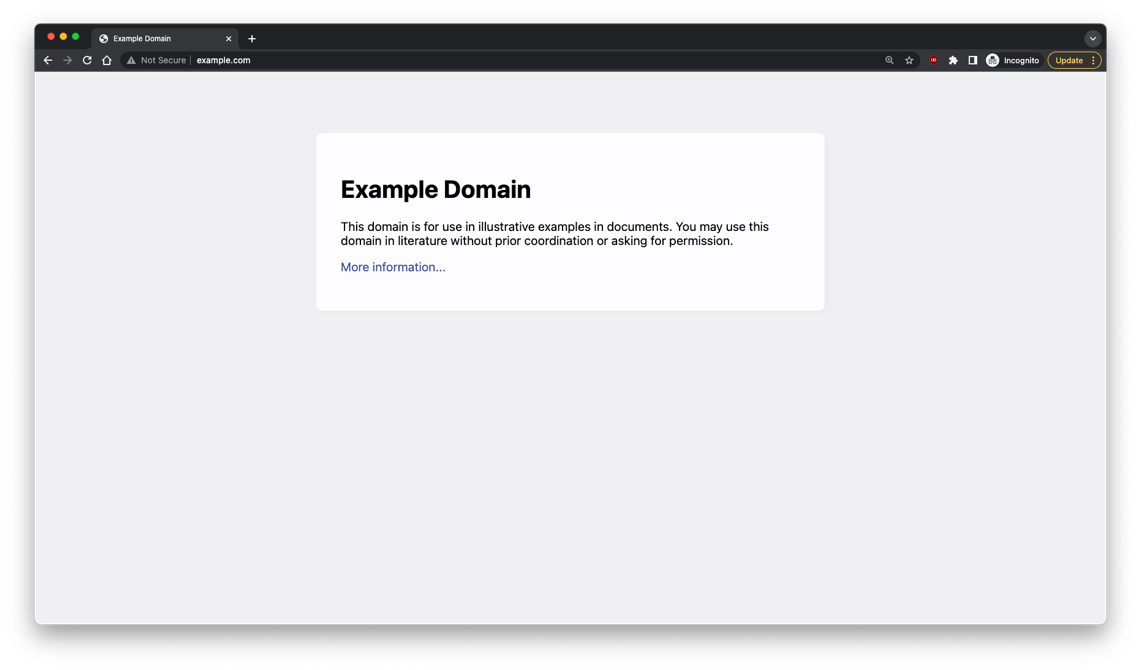

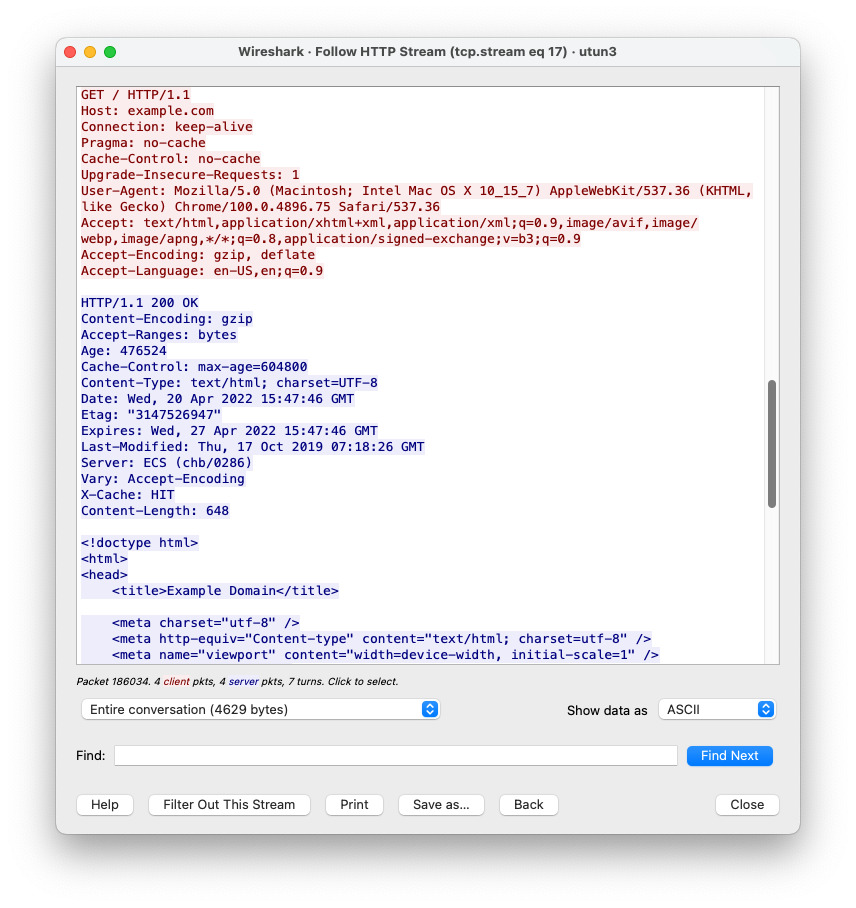

All protocols define a structured way for data to be exchanged. In the case of HTTP, it guides how the “conversation” between a client (web browser) and a server (the website) should be structured, including how data should be requested, and the format of the server’s response. For example, when I visit the website http://www.example.com, my browser will display a webpage (Figure 1). However the full “conversation” between my computer and the webserver contains more information that is typically not displayed to the user (Figure 2).

Figure 1: The rendered HTML of the http://www.example.com web page as displayed in a browser. Screenshot by author.

Figure 2: The text of the HTTP conversation between the client (red) and the server (blue) as viewed via the Wireshark network traffic analysis application. Screenshot by author.

The HTTP “conversation” includes a response code that the server returns along with the response itself. Response codes make the conversation between client and server both machine and human readable and indicate whether the request was successful or not.[31] In the above example, the server returned the code “200 – OK” to indicate that it accepted the request and returned the page content to my browser.

All HTTP response codes are a 3 digit number, and are grouped together into 5 classes of possible outcomes:

1. Informational responses (100-199)

2. Success responses (200-299)

3. Redirect notices (300-399)

4. Client-side error messages (400-499)

5. Server-side error messages (500-599)

The definition of a specific response code demonstrates there is an imagined use case, a scenario that could feasibly happen. For example, the “404 – Not Found” code shows that the developers of the protocol envisioned the possibility of a client requesting a resource that the server was not able to locate. The “403 – Forbidden” code indicates that controlling access and requiring authentication for certain content is prioritized as a way that the Web should work.

Furthermore, it is worth lingering a moment on the response code classes and the possible error types. When an HTTP request is unsuccessful—that is, when the requested content is not returned—responsibility can lie in one of two places. It is either an error on the part of the client (any 4XX code) or an error on the part of the server (any 5XX code). If I write a script to send thousands of requests within just a few seconds, the server might respond with the error code 429 (Too Many Requests). It’s my fault (the client) that the request failed. If dynamic code (such as PHP or Ruby) execution fails on the server, I may see a response code of 500 (Internal server error). The failure happened on the server’s side. But what about if the request fails as the result of outside influence? When content is withheld as a result of a legal request, it isn’t necessarily either the client or the server who is to blame. The protocol is built on the assumption that only the client and the server drive the HTTP conversation. But as the prevalence of geoblocking indicates, it is possible for external powers such as state governments and corporations to restrict the flow of content online.

The fact that the eventual code for legally restricted content was eventually placed in the 4XX class of response codes categorizes such situations as an error that occurred on the part of the client. At the level of the protocol, the content is not unavailable because of a government’s law. It is unavailable because the user made the error of requesting restricted content. In her discussion of the “404 – Not Found” response code, Lisa Gitelman states, “Error 404 does not specify who committed or what caused the error to occur.”[32] While this may be true for how most people encounter such errors, at the level of the protocol it is clear who is to blame for the error. This is, in part, a pedantic distinction to be made. But at the same time, it is important to consider how the protocols and code of the Web are used here to extend neoliberal logics of individual responsibilities onto the user, all while downplaying the continued role of government regulation. In fact, this potential situation of blaming the user for government action was considered by early proponents of an HTTP code for censorship.

Until the mid-2000s, however, there was not an HTTP response code that acknowledged the possibility of content being withheld for legal reasons. As Chris Applegate wrote in his blog, “there is no HTTP code for censorship.”[33] The lack of a specific response code for these scenarios perhaps represents the early idealistic visions of the Web as a virtual space freed from the restrictive laws of the “real” world. However, by the late 2000s it had become apparent that nation-states did still have significant power to control the flow of media in online spaces and that governments were engaged in practices of censoring Web content and restricting online access.[34] In 2012, Terence Eden noted that his ISP was intercepting certain HTTP requests and returning a “403 – Forbidden” code, which in his view was an inaccurate characterization of the perceived censorship that was taking place. In his view censorship was an “existential threat” to the Web, and so Eden suggested that in cases of censorship, servers should return “HTTP 911 – Internet Emergency,” an entirely new class of response codes to represent the severity of the threat of censorship.[35]

The 9XX code block has yet to be implemented, and when Tim Bray submitted a proposal to the IETF HTTP working group based on Eden’s suggestions, he proposed that when content is withheld for legal reasons, the server should return HTTP code 451, a not-so-subtle allusion to Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, a dystopian novel about book burning and censorship.[36] The HTTP 451 response code was proposed by Bray in 2012, and after several rounds of revision and discussion, was formally approved by the IETF and adopted as an official HTTP standard in 2016.[37] Specifically, the standard specifies that the 451 code is intended “for use when a server operator has received a legal demand to deny access to a resource or to a set of resources that includes the requested resource.”[38] According to the written standard, a server should include within its response information about the entity that is implementing the block, to clarify whether it is the website owner, the ISP, or someone else that received the legal demand. Additionally, the response body should include an explanation of the legal demand—such as the relevant law or regulation. The use of the word “should” is significant, as the IETF specifically defines this term alongside others such as “must,” “may,” and “recommend.”[39] Under these definitions, including an explanation of the legal demand is not an absolute requirement, but there are only a few circumstances when not including such explanation would be preferable. In practice, however, such explanations are few and far between.

The written standard for the HTTP 451 response code provides a mechanism by which the power and legal authority of a nation can be written into the technical underpinnings of the Web itself. Through a full stack analysis and by looking to the protocols and codes upon which the Web operates, we can see how access and flows of content can still be geographically constrained even in a virtual space that was once imagined to be borderless. That said, we must be cautious of reading too much into the written standard and acknowledge that the actual implementation of the HTTP 451 code may greatly vary in practice. Tim Bray had noted such possibilities, and that “It is possible that certain legal authorities might wish to avoid transparency, and not only demand the restriction of access to certain resources, but also avoid disclosing that the demand was made.”[40] Additionally, the reality of the Web has long been a culture of “rough consensus and running code,” and website operators have often employed IEFT standards in ways that may be technically incorrect, but still enable the Web to function. It is with these caveats in mind that I sought out examples of how the HTTP 451 status has been used in actual website implementations.

Unavailable for Legal Reasons – HTTP Error Codes in The Real World

One of the challenges of studying the Web is the sheer volume of content that a researcher may find herself sifting through. While search engines and databases may offer some utility in keeping up with the continual generation of new content, these tools are best suited for searching for the contents of a webpage. Given my full stack analysis, I would need to search the underlying HTTP traffic, which is generally not indexed information. To find real-world examples of the HTTP 451 code, I turned to two sources. First, I examined public announcements of planned implementations to how the status code has been discussed by website operators. Second, I used a large-scale IP scanning tool to identify public-facing HTTP servers that return HTTP 451 codes.

Planned Uses of the HTTP 451 Code

Coming across an actual HTTP 451 response code during the day-to-day practices is unpredictable. Rather than rely on serendipity to encounter such examples, I searched for discussions of the HTTP response code rather than the actual code itself. As one example, in the months following the adoption of the HTTP 451 standard, the code repository platform Github announced that it was now officially supporting the standard in the GitHub API (Application Programming Interface). In a post on the GitHub developer blog, they explained that their service would no longer use the “403 – Forbidden” code and instead “now respond with a 451 status code for resources it has been asked to take down due to a DMCA [Digital Millennium Copyright Act] notice.”[41] The DMCA itself is an important reminder that instances of government power are frequently connected to corporate interests as well. Yes, the DMCA is a law enacted and enforced by the U.S. government. But the law is written to serve the interests of private copyright holders, and enforcement is typically triggered by a corporation submitting a formal complaint and takedown request. The GitHub developer blog post shows that for GitHub, the new HTTP standard was a way to enact its responses to DMCA requests within code itself.

Because GitHub is a commonly used service for open-source development, I used Google to perform a site-specific search to find examples of open source projects that included discussions of the status code. By performing a Google query for “http 451 site:github.com” I limited my results to those contained on the GitHub site, and found several examples of projects discussing how to handle this HTTP response code. For example, the open-source social network service Mastodon had to figure out how to handle the problems of nation-specific legal implementations and compliance. In the code issues forum, user irlcatgirl acknowledged the complexity of adding HTTP 451 support to Mastodon, explaining that “Users do have the legal right to appeal here in the US so it's complicated because I'm legally required to let them restore if they send a counter-notice but have no ability to restore the content once deleted.”[42] In other projects, HTTP 451 implementation was proposed in early 2016, but the discussion remains stale and unresolved six years later.[43] In one case, the developers specifically chose to not use the HTTP 451 code given concerns that it would be seen as “professional,” opting instead to use “405 – Method Not Allowed” or “501 – Not Implemented,” despite “451 – Unavailable for Legal Reasons” being a legitimate IETF standard.[44] These examples each demonstrate a different approach to ensure and enable legal compliance, but taken collectively emphasize the ongoing influence of law and the state even in “borderless” online contexts. Furthermore, the fact that such discussions concern the software code and not the application or page content are a reminder that the full cultural significance of the Web can be found across multiple layers of the stack.

These examples, however, are still somewhat speculative and have a limited ability to show us the interaction between government and code. They remain partially detached from the “real world” and do not necessarily represent how an actual user might encounter these implementations of the HTTP 451 code during their day-to-day Web browsing practices. In the next section, I explain one possible means of performing a full stack analysis by collecting and parsing large datasets and snapshots of the World Wide Web.

Parsing the Censys.io Database

To find examples of current HTTP 451 implementations and to view the full HTTP conversation, I wrote a series of python scripts to automatically perform queries on the Censys dataset. Censys is an information security research project which performs daily port scans on the entire IPv4 address space.[45] In (marginally more) simple terms, Censys queries every publicly accessible IP address and checks for common running services and indexes the results into a searchable database. The Censys data includes details on HTTP servers, including the response code and response body that they return. I use the Censys API to automatically perform searches, for publicly accessible servers that are providing HTTP access and returning a response code of 451 gather daily statistics, and save copies of the fully HTTP response body.[46] These scripts continue to run on a regular basis, and in addition to the examples I discuss below, up-to-date data is publicly accessible at https://http451.info/. By collecting information from multiple layers of the Web stack, I am able to view both the page content that a user might view and details about the underlying protocol too.

First, I collected aggregate counts of the HTTP response codes within the Censys data set each day for one week in April 2022. For considerations of space, I only include here a handful of the most common response codes.

TABLE 1: Average Query Frequencies from One Week of Censys Scanning

Code: |

200 |

301 |

307 |

403 |

404 |

451 |

500 |

Description: |

OK |

Moved Permanently |

Temporary Redirect |

Forbidden |

Not Found |

Unavailable for Legal Reasons |

Internal Server Error |

Mean Freq. of Response |

463,048,852 |

250,260,249 |

2,986,422.11 |

82,598,138.9 |

104,144,596 |

14,155.11 |

11,631,340.6 |

Unsurprisingly, most responses are “200 – OK,” indicating that most public-facing HTTP servers are successfully serving content. The large number of 301 and 307 codes is also unsurprising, as these redirect codes are often used when a website operator redirects plain HTTP requests to use the more secure HTTPS version of the standard. Given the short timespan of this data and the wide fluctuation in accessible Web servers, the precise values of each code are not significant. However, what is notable is that the number of HTTP 451 codes is a whole order of magnitude less than other codes. While there are tens or hundreds of millions of HTTP servers returning 200, 301, 307, 403, 404, and 500, there are mere tens of thousands of 451 responses.

Despite the HTTP 451 standard having been adopted six years ago, it has yet to be implemented at large scale. An optimistic reading of this may be that there is actually very little legal action requiring website operators to withhold content from certain reasons. The pessimistic view is that such restrictions are still taking place, but in ways that are not as readily apparent. For example, an Internet Service Provider may silently intercept requests for a certain site and return a “404 – Not Found” or “403 – Forbidden” code before the request even reaches the server. This may also mean that in cases of geoblocking, a server is still returning a 200 - OK response. Instead of a 451, the response contains a message about unavailable content rather than the content the user was seeking out, which is frequently the case when a video streaming platform restricts its content to certain regions of the world.[47] Additionally, it may simply be the case that most online geoblocking is not actually the result of legal action. Online geoblocking is common practice and has been acknowledged and studied widely, despite the relative paucity of 451 response codes suggesting otherwise.[48] Perhaps the majority of online content restrictions are the result of corporate interests, and not necessarily that of governments or law. When major platforms such as YouTube or Netflix they display a “This content is not available in your country” page, it would likely be inaccurate to use an HTTP 451 code. The content is not unavailable due to legal restrictions; it is unavailable due to the platform’s business strategies. This is an important reminder that attention only to underlying code or only the visible content may miss important context; a benefit of the full stack analytical frame is that it looks across multiple layers to possibly reveal such instances to the researcher.

In addition to the aggregate statistics discussed above, I also used a series of scripts to scrape specific information from the HTTP servers that were responding the 451 code. I performed a query on the Censys dataset for HTTP services that responded with the 451 code, but also had an HTTP response size greater than 0.[49] By viewing the resulting HTML content in a Web browser, I was able to collect examples of the actual content that a user might see in their browser when they encounter an HTTP 451 error.

As discussed previously, the HTTP 451 standard states that one “should” provide information about the entity performing the block, as well as an explanation of the block reason for the user to understand. The HTTP responses that I examined take this “should” directive very loosely and provide very little information about the reasons that the content on the page is not available. There were no examples of a server naming the blocking entity within the HTTP response header, leaving it unclear whether it was the website operator that received the legal request or if it was an Internet Service Provider or other intermediary.[50]

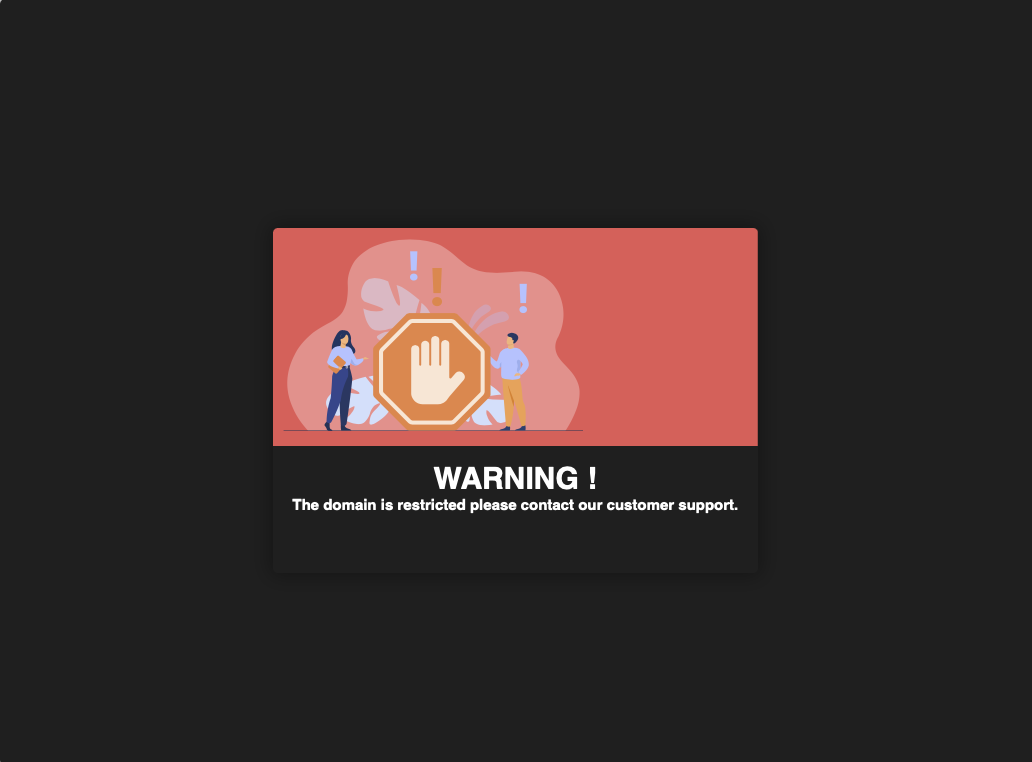

While there were examples of the HTTP response body containing more information, there is still very little meaning explanation given to the user. Many response bodies were a single line of text containing “451,” “not authorized,” or simply “error.” None of these responses adequately explain to a user the reason for content being inaccessible, and for a user who is not familiar with HTTP response codes, they are unlikely to even associate such a message with legal content restrictions. In other examples, such as Figure 3, there was a full Web page delivered with a slightly longer message, but still with little clarity or explanation provided for the user.

Figure 3: The HTTP response body retrieved from 3.251.164.218 on April 19, 2022. Screenshot by author.

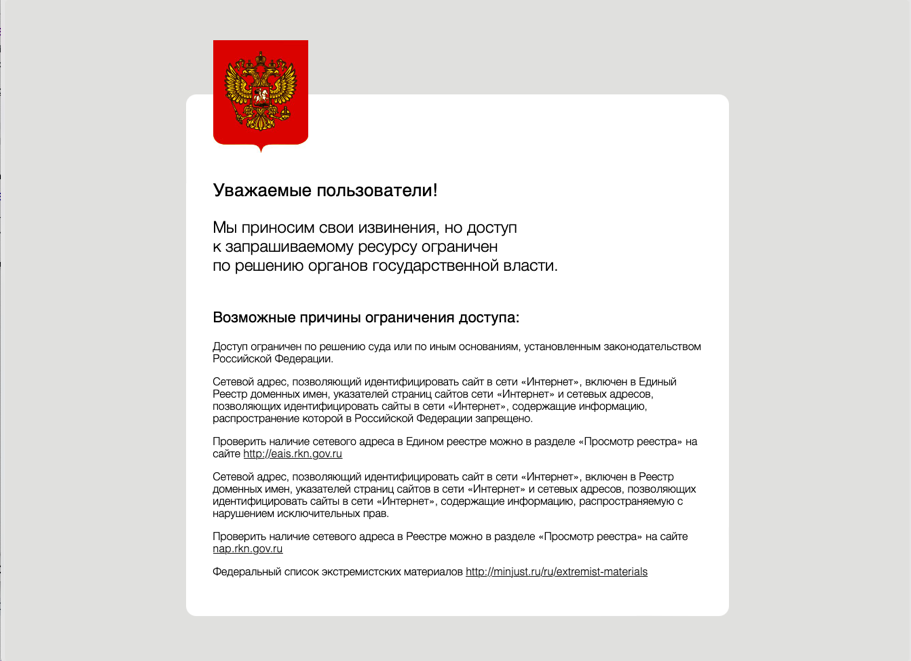

Many of the response bodies did contain a longer written explanation of the reason that content was being blocked. These explanations were often not in English, with Russian being among the most frequently occurring language. This suggests that while many Russian sites are technically still publicly accessible, the government continues to exercise significant control over what media content can be accessed. Google Translate’s approximation of the webpage shown in Figure 4 includes phrases such as “Access is restricted by a court decision or on other grounds established by the legislation of the Russian Federation” and includes hyperlinks to a Russian government website with further information on the legal restrictions.

Figure 4: The HTTP response body retrieved from 217.107.192.51 on April 19, 2022. Screenshot by author.

In the handful of examples of actual HTTP 451 responses that I have discussed above, it is apparent that there is often very little explanation of the legal reasoning behind content blocking. This is a reminder that while geoblocking is a common feature of the modern Web, there is a tendency to downplay its role and significance. The use of an HTTP 451 response code tends to obfuscates whose interests are being served when Web content is restricted. The code suggests that when content is inaccessible it is a failure of technology, and not the result of corporate interests and government power enacted within code. And while some of the above examples contain cryptic messages and unhelpful explanations, I suppose it is at very least some acknowledgement that content is being withheld for legal reasons, rather than providing a more inaccurate error such as “404 - Not Found” or terminating the connection to the server entirely. The HTTP 451 response code along with the response body that is returned to the user represents the ability of governments to exert their power in online spaces. The government action is seen not just in the page content, but reflected in the lower levels of code as well

Conclusions

The codes and protocols upon which day-to-day encounters with new media technologies remain fairly hidden and unknown to most users. But adopting the approach of full stack analysis can reveal how cultural meanings can arise from multiple levels of a given technology. In the context of HTTP, the 451 response code is one example of how traditional institutions of power, such as national governments, continue to exert influence even in the “borderless” space of the Web. The HTTP 451 response code transfers state power into online spaces and embeds it within the very codes and protocols of the Web. Additionally, the code’s location within the 4XX class of response codes enables it to be an allusion to Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451, but has the side effect of blaming the user for something that is the result of government action.

The 451 response code has been a formal part of the HTTP standard for several years, but my parsing of the Censys scan dataset indicates that it is yet to have been widely implemented. There are only a few tens of thousands of hosts returning a 451 code, a miniscule proportion of the hundreds of millions of hosts on the public Internet. This paucity is likely an indication that the restriction of online content is not merely the result of government action, but may be through the actions of private corporations, which is less likely to be reflected in the 451 code. This underscores the utility of analyzing the Web across multiple layers of the stack, rather than homing in on a single textual layer.

The HTTP 451 response code is an indicator of the continued power of nation states to restrict the flow of media in online settings. Despite claims of being “world wide,” the Web is still segmented and differently experienced by users across the world. Website operators may face many challenges in determining if specific national and regional laws should be applied, and how to do so. The full stack analytical approach offers Web researchers a mechanism to locate these indications of the state’s continued power to better understand how code and law become intertwined.[51] Full stack analyses may be useful to other Internet researchers, but the flexibility of the approach means that it may offer generative insights to studies of other forms of new media as well. By looking across multiple layers of the stack, this method shows how online content blocking can be directly made visible to the user but becomes inscribed within code and protocols as well. The Web is not, and perhaps never has been, truly global. The individual nation-state still matters and exercises its power within online spaces—even at the level of the protocol—to control where and how media can move.

Works Cited

Andrejevic, Mark. “The Work of Being Watched: Interactive Media and the Exploitation of Self-Disclosure.” Critical Studies in Media Communication 19, no. 2 (June 2002): 230–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/07393180216561.

Ankerson, Megan Sapnar. Dot-Com Design: The Rise of a Usable, Social, Commercial Web. New York: New York University Press, 2018.

Applegate, Chris. “There Is No HTTP Code for Censorship.” qwghlm.co.uk, December 9, 2008. https://www.qwghlm.co.uk/2008/12/09/there-is-no-http-code-for-censorship/.

Bamman, David, Brendan O’Connor, and Noah Smith. “Censorship and Deletion Practices in Chinese Social Media.” First Monday, March 4, 2012. https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v17i3.3943.

Barlow, John Perry. “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace.” Electronic Frontier Foundation, February 8, 1996. https://www.eff.org/cyberspace-independence.

Benjamin, Ruha. Race after Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Medford, MA: Polity, 2019.

Bradbury, Ray. Fahrenheit 451. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003.

Bradner, Scott O. “Key Words for Use in RFCs to Indicate Requirement Levels.” Request for Comments. Internet Engineering Task Force, March 1997. https://doi.org/10.17487/RFC2119.

Bray, Tim. “An HTTP Status Code to Report Legal Obstacles.” Request for Comments. Internet Engineering Task Force, February 2016. https://doi.org/10.17487/RFC7725.

———. “An HTTP Status Code to Report Legal Obstacles (Draft).” Internet Draft. Internet Engineering Task Force, June 11, 2012. https://www.ietf.org/archive/id/draft-tbray-http-legally-restricted-status-00.txt.

Brock, André L. Distributed Blackness: African American Cybercultures. Critical Cultural Communication. New York: New York University Press, 2019.

Brügger, Niels. The Archived Web: Doing History in the Digital Age. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2018.

Carveth, Rod, and J. Michel Metz. “Frederick Jackson Turner and the Democratization of the Electronic Frontier.” The American Sociologist 27, no. 1 (March 1, 1996): 72–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02691999.

Couldry, Nick, and Ulises Ali Mejias. The Costs of Connection: How Data Is Colonizing Human Life and Appropriating It for Capitalism. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2019.

Department of Justice Office of Public Affairs. “United States Seizes Domain Names Used by Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps.” Press Release. Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, October 7, 2020. https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/united-states-seizes-domain-names-used-iran-s-islamic-revolutionary-guard-corps.

Durumeric, Zakir, David Adrian, Ariana Mirian, Michael Bailey, and J. Alex Halderman. “A Search Engine Backed by Internet-Wide Scanning.” In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, 542–53. CCS ’15. New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2015. https://doi.org/10.1145/2810103.2813703.

Eden, Terence. “There Is No HTTP Code for Censorship (but Perhaps There Should Be).” Terence Eden’s Blog (blog), June 8, 2012. https://shkspr.mobi/blog/2012/06/there-is-no-http-code-for-censorship-but-perhaps-there-should-be/.

Elkins, Evan. Locked out: Regional Restrictions in Digital Entertainment Culture. Critical Cultural Communication. New York: New York University Press, 2019.

Ellcessor, Elizabeth. Restricted Access: Media, Disability, and the Politics of Participation. Postmillennial Pop. New York: New York University Press, 2016.

Gillespie, Tarleton. Wired Shut: Copyright and the Shape of Digital Culture. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2007.

Gitelman, Lisa. Always Already New: Media, History, and the Data of Culture. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2006.

gjtorikian. “The 451 Status Code Is Now Supported.” GitHub Developer, March 17, 2016. https://developer.github.com/changes/2016-03-17-the-451-status-code-is-now-supported/.

irlcatgirl. “Mark Status/Account as HTTP 451 Not Available For Legal Reasons.” GitHub Repository. Mastodon/Mastodon, February 18, 2022. https://github.com/mastodon/mastodon/issues/17591.

jcspencer. “Implement RFC 7725 HTTP 451 Error Code.” GitHub Repository. Ninenines/Cowboy, March 27, 2016. https://github.com/ninenines/cowboy/issues/965.

Kosseff, Jeff. The Twenty-Six Words That Created the Internet. Ithaca [New York]: Cornell University Press, 2019.

Lee, Jyh-An, and Ching-U Liu. “Forbidden City Enclosed by the Great Firewall: The Law and Power of Internet Filtering in China.” Minnesota Journal of Law, Science and Technology 13, no. 1 (2012): 125–52.

Lessig, Lawrence. Code Version 2.0. New York: Basic Books, 2006.

Lobato, Ramon. Netflix Nations: The Geography of Digital Distribution. Critical Cultural Communication. New York: New York University Press, 2019.

Lobato, Ramon, and James Meese, eds. Geoblocking and Global Video Culture, 2015.

Manovich, Lev. Software Takes Command: Extending the Language of New Media. International Texts in Critical Media Aesthetics. New York ; London: Bloomsbury, 2013.

Monea, Alexander. The Digital Closet: How the Internet Became Straight. Strong Ideas Series. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2022.

Mozilla. “Evolution of HTTP.” MDN Web Docs, March 19, 2022. https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/HTTP/Basics_of_HTTP/Evolution_of_HTTP.

———. “HTTP Response Status Codes.” MDN Web Docs, February 18, 2022. https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/HTTP/Status.

Noble, Safiya Umoja. Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism. New York: New York University Press, 2018.

Parks, Lisa, and Nicole Starosielski, eds. Signal Traffic: Critical Studies of Media Infrastructures. The Geopolitics of Information. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2015.

Peters, Benjamin. How Not to Network a Nation: The Uneasy History of the Soviet Internet. Information Policy. Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press, 2016.

Pettis, Ben. Http451-Tracker, 2022. https://github.com/bpettis/http451-tracker.

Proton Technologies AG. “Cookies, the GDPR, and the EPrivacy Directive.” GDPR.eu, May 9, 2019. https://gdpr.eu/cookies/.

Rheingold, Howard. The Virtual Community: Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier. Revised Edition. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2000.

rhuss. “Node Templates Default for Unsupported HTTP Method · Issue #596 · Knative-Sandbox/Kn-Plugin-Func.” GitHub Repository. box/kn-plugin-funct, October 20, 2021. https://github.com/knative-sandbox/kn-plugin-func/issues/596.

Stallings, William. “The Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) Model and OSI-Related Standards.” In Handbook of Computer-Communications Standards. Macmillan, 1987. http://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.5555/29355.

Starosielski, Nicole. The Undersea Network. Sign, Storage, Transmission. Durham: Duke University Press, 2015.

Sterne, Jonathan. MP3: The Meaning of a Format. Sign, Storage, Transmission. Durham: Duke University Press, 2012.

Subramanian, Ramesh. “The Growth of Global Internet Censorship and Circumvention: A Survey.” SSRN Scholarly Paper. Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network, October 31, 2011. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2032098.

Trimble, Marketa. “Geoblocking, Technical Standards and the Law.” In Geoblocking and Global Video Culture, edited by Ramon Lobato and James Meese, 54–63, 2015.

Notes:

[1] John Perry Barlow, “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace,” Electronic Frontier Foundation, February 8, 1996, https://www.eff.org/cyberspace-independence.

[2] Ray Bradbury, Fahrenheit 451 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 2003).

[3] Howard Rheingold, The Virtual Community: Homesteading on the Electronic Frontier, Revised Edition (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2000).

[4] See, for example: Mark Andrejevic, “The Work of Being Watched: Interactive Media and the Exploitation of Self-Disclosure,” Critical Studies in Media Communication 19, no. 2 (June 2002): 230–48, https://doi.org/10.1080/07393180216561; Nick Couldry and Ulises Ali Mejias, The Costs of Connection: How Data Is Colonizing Human Life and Appropriating It for Capitalism (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2019); Safiya Umoja Noble, Algorithms of Oppression: How Search Engines Reinforce Racism (New York: New York University Press, 2018).

[5] Proton Technologies AG, “Cookies, the GDPR, and the EPrivacy Directive,” GDPR.eu, May 9, 2019, https://gdpr.eu/cookies/.

[6] Mozilla, “Evolution of HTTP,” MDN Web Docs, March 19, 2022, https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/HTTP/Basics_of_HTTP/Evolution_of_HTTP.

[7] Tim Bray, “An HTTP Status Code to Report Legal Obstacles,” Request for Comments (Internet Engineering Task Force, February 2016), https://doi.org/10.17487/RFC7725.

[8] Barlow, “A Declaration of the Independence of Cyberspace.”

[9] Rod Carveth and J. Michel Metz, “Frederick Jackson Turner and the Democratization of the Electronic Frontier,” The American Sociologist 27, no. 1 (March 1, 1996): 73, https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02691999.

[10] Rheingold, The Virtual Community.

[11] Lisa Gitelman, Always Already New: Media, History, and the Data of Culture (Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2006), 5.

[12] Alexander Monea, The Digital Closet: How the Internet Became Straight, Strong Ideas Series (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2022).

[13] Elizabeth Ellcessor, Restricted Access: Media, Disability, and the Politics of Participation, Postmillennial Pop (New York: New York University Press, 2016).

[14] Ruha Benjamin, Race after Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code (Medford, MA: Polity, 2019); André L. Brock, Distributed Blackness: African American Cybercultures, Critical Cultural Communication (New York: New York University Press, 2019); Noble, Algorithms of Oppression.

[15] Megan Sapnar Ankerson, Dot-Com Design: The Rise of a Usable, Social, Commercial Web (New York: New York University Press, 2018), 196.

[16] For example, see: Department of Justice Office of Public Affairs, “United States Seizes Domain Names Used by Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps,” Press Release (Washington, DC: US Department of Justice, October 7, 2020), https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/united-states-seizes-domain-names-used-iran-s-islamic-revolutionary-guard-corps; Proton Technologies AG, “Cookies, the GDPR, and the EPrivacy Directive.”

[17] Benjamin Peters, How Not to Network a Nation: The Uneasy History of the Soviet Internet, Information Policy (Cambridge, MA, USA: MIT Press, 2016).

[18] Tarleton Gillespie, Wired Shut: Copyright and the Shape of Digital Culture (Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press, 2007).

[19] Jeff Kosseff, The Twenty-Six Words That Created the Internet (Ithaca [New York]: Cornell University Press, 2019).

[20] Marketa Trimble, “Geoblocking, Technical Standards and the Law,” in Geoblocking and Global Video Culture, ed. Ramon Lobato and James Meese, 2015, 61.

[21] Evan Elkins, Locked out: Regional Restrictions in Digital Entertainment Culture, Critical Cultural Communication (New York: New York University Press, 2019), 43.

[22] Lawrence Lessig, Code Version 2.0 (New York: Basic Books, 2006).

[23] Gitelman, Always Already New.

[24] Emphasis in original. Lev Manovich, Software Takes Command: Extending the Language of New Media, International Texts in Critical Media Aesthetics (New York ; London: Bloomsbury, 2013), 15.

[25] Jonathan Sterne, MP3: The Meaning of a Format, Sign, Storage, Transmission (Durham: Duke University Press, 2012).

[26] William Stallings, “The Open Systems Interconnection (OSI) Model and OSI-Related Standards,” in Handbook of Computer-Communications Standards (Macmillan, 1987), http://dl.acm.org/doi/abs/10.5555/29355.

[27] Niels Brügger, The Archived Web: Doing History in the Digital Age (Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2018).

[28] Lisa Parks and Nicole Starosielski, eds., Signal Traffic: Critical Studies of Media Infrastructures, The Geopolitics of Information (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2015); Nicole Starosielski, The Undersea Network, Sign, Storage, Transmission (Durham: Duke University Press, 2015).

[29] Mozilla, “Evolution of HTTP.”

[30] Manovich, Software Takes Command, 15.

[31] Mozilla, “HTTP Response Status Codes,” MDN Web Docs, February 18, 2022, https://developer.mozilla.org/en-US/docs/Web/HTTP/Status.

[32] Gitelman, Always Already New, 132.

[33] Chris Applegate, “There Is No HTTP Code for Censorship,” qwghlm.co.uk, December 9, 2008, https://www.qwghlm.co.uk/2008/12/09/there-is-no-http-code-for-censorship/.

[34] David Bamman, Brendan O’Connor, and Noah Smith, “Censorship and Deletion Practices in Chinese Social Media,” First Monday, March 4, 2012, https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v17i3.3943; Jyh-An Lee and Ching-U Liu, “Forbidden City Enclosed by the Great Firewall: The Law and Power of Internet Filtering in China,” Minnesota Journal of Law, Science and Technology 13, no. 1 (2012): 125–52; Ramesh Subramanian, “The Growth of Global Internet Censorship and Circumvention: A Survey,” SSRN Scholarly Paper (Rochester, NY: Social Science Research Network, October 31, 2011), https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2032098.

[35] Terence Eden, “There Is No HTTP Code for Censorship (but Perhaps There Should Be),” Terence Eden’s Blog (blog), June 8, 2012, https://shkspr.mobi/blog/2012/06/there-is-no-http-code-for-censorship-but-perhaps-there-should-be/.

[36] Tim Bray, “An HTTP Status Code to Report Legal Obstacles (Draft),” Internet Draft (Internet Engineering Task Force, June 11, 2012), https://www.ietf.org/archive/id/draft-tbray-http-legally-restricted-status-00.txt.

[37] Bray, “An HTTP Status Code to Report Legal Obstacles.”

[38] Bray.

[39] Scott O. Bradner, “Key Words for Use in RFCs to Indicate Requirement Levels,” Request for Comments (Internet Engineering Task Force, March 1997), https://doi.org/10.17487/RFC2119.

[40] Bray, “An HTTP Status Code to Report Legal Obstacles.”

[41] gjtorikian, “The 451 Status Code Is Now Supported,” GitHub Developer, March 17, 2016, https://developer.github.com/changes/2016-03-17-the-451-status-code-is-now-supported/.

[42] irlcatgirl, “Mark Status/Account as HTTP 451 Not Available For Legal Reasons,” GitHub Repository, Mastodon/Mastodon, February 18, 2022, https://github.com/mastodon/mastodon/issues/17591.

[43] jcspencer, “Implement RFC 7725 HTTP 451 Error Code,” GitHub Repository, Ninenines/Cowboy, March 27, 2016, https://github.com/ninenines/cowboy/issues/965.

[44] rhuss, “Node Templates Default for Unsupported HTTP Method · Issue #596 · Knative-Sandbox/Kn-Plugin-Func,” GitHub Repository, box/kn-plugin-funct, October 20, 2021, https://github.com/knative-sandbox/kn-plugin-func/issues/596.

[45] Zakir Durumeric et al., “A Search Engine Backed by Internet-Wide Scanning,” in Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGSAC Conference on Computer and Communications Security, CCS ’15 (New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2015), 542–53, https://doi.org/10.1145/2810103.2813703.

[46] Censys Search is a paid service, and the free tier only provides limited API access. I requested, and received, researcher access to the Censys API, which provides increased API rate limits and other features for research purposes. My scripts and additional information are available online as open-source code: Ben Pettis, Http451-Tracker, 2022, https://github.com/bpettis/http451-tracker.

[47] Ramon Lobato, Netflix Nations: The Geography of Digital Distribution, Critical Cultural Communication (New York: New York University Press, 2019).

[48] Ramon Lobato and James Meese, eds., Geoblocking and Global Video Culture, 2015.

[49] The specific query syntax for the Censys search API was "services.http.response.status_code=451 AND NOT services.http.response.body_size=0"

[50] I am only able to include a few example response bodies here. Additional examples and the full dataset is available at https://http451.info

[51] Lessig, Code Version 2.0.